Client

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA)

My Role

User Research | Prototyping | UI Design | Brand

Challenge

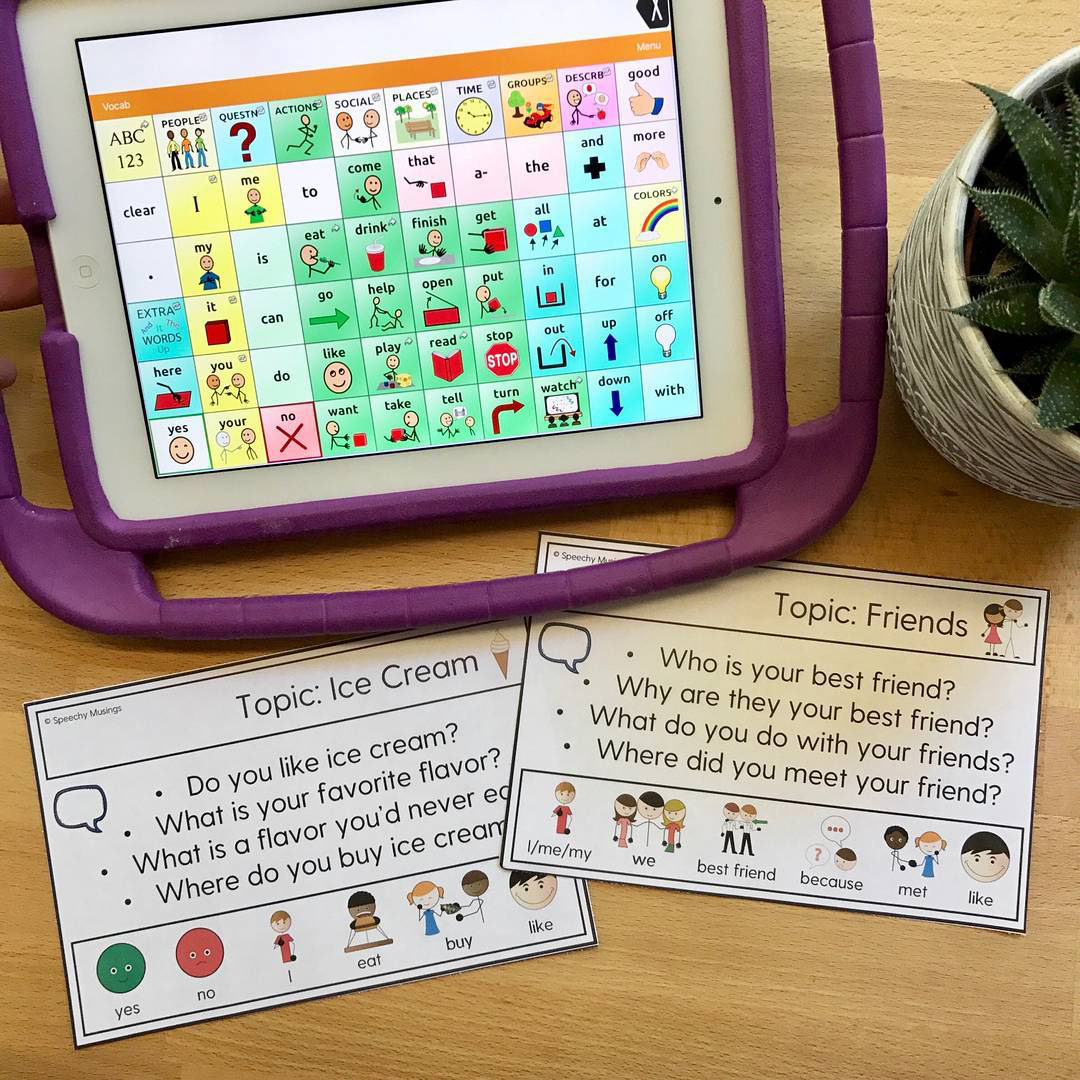

AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) devices assist verbal apraxic individuals with communicating their needs when spoken words are not available. Based on PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System), developed in 1985, very little UX has evolved since its adaptation to the world of apps and internet.

An overwhelming selection of conversational starter cards leaves many in the non-verbal community frustrated, but none more than those lacking the cognitive skills to independently operate these devices' complex sentence builders, according to their speech therapists and caregivers. Consider this comment from one such father:

"Proloquo2go is like throwing 1,000 flash cards on the floor and asking a kid to build a sentence. The interface is a mess of folders nested with folders and finding what you want among thousands of stick figures is near impossible. The level of customization necessary for each individual makes the interface design even more perplexing. This is not an easy app to customize. It's basically a confusing melange of flash cards. My daughter just stims with it and creates two minute-long run on nonsensical messages. I can't stand this app."

A typical AAC Device leaves users not knowing where to begin

This sentiment is shared by Speech Pathologists of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), who agree that current AAC apps are far too complicated for the cognitively impaired to use for independently expressing their basic human needs to therapists and caregivers.

Discovery

Competitive analysis of the three top players in the AAC app space, Proloquo2Go, TouchChat and SonoFlex, exposed commonalities that left me scratching my head - how do all of these products, considered to be the best in their class, get away with flouting even the most common conventions of user experience? 1.) Cramming their home screens with an overwhelming selection of choices, rather than allowing their users to drill in, 2.) ignoring long accepted navigational paradigms, and 3.) avoiding the use of conventional symbols to express emotions, in favor of confusing metaphors and stick figures that have been the bane of AAC users for time immemorial, according to users, caregivers, teachers and speech therapists who were interviewed.

I was given permission to observe interactions between verbal apraxic high school students, both with and without accompanying cognitive disabilities, and their service providers in the Special Needs Program of the New Braunfels Independent School District during their use of Proloquo2Go and SonoFlex AAC devices. I witnessed a disparity of reactions between those without cognitive disabilities, who often were able to lead conversations with the aid of their AAC device, and those with cognitive disabilities, who found it difficult to follow even hand over hand instruction from their caregivers, resulting often in emotional outbursts as a means of expression. Afterwards, feelings expressed by therapist, instructors and volunteers who were interviewed contained a similar thread:

“If only there were a way for us to understand one another before emotions take over.”

This simple plea would become the starting point for the app that was about to take shape. What if we began with emotions? What is the one thing everyone in the world uses when we can't find words to express how we feel?

The beloved Emoji... Often better understood than actual human facial expressions, according to an overwhelming majority of autistic individuals and service providers interviewed.

Excited by this epiphany, I began to quickly scribble out what an app that uses emojis as a conversational starting point might look like, and noted the following concerns:

• Some cognitively impaired individuals lack object permanence. How will they react to a page turn or even scrolling away from their progress made in a sentence builder?

• How will it help expand conversations beyond the discovery of feelings?

• What will someone with cognitive disability do if they make a mistaken selection?

• How will both user and caregiver reach a level of success together while providing the user with a sense of independence?

This was not going to be a Swiss Army app, it had to remain simple. Its purpose would be to fill the gap for those who have been unable to use AAC devices to express their most basic human needs:

"I feel..." "I want..."

Hand drawings, using a Tombow Duel Brush Pen & a gray Crayola marker I borrowed from my Daughter :)

My research told me that a solution would need to provide a way for the user to build up to a conversation, rather than overwhelm them with choices. It also needed to allow the user to confirm their selections or go back, a feature that is either missing or poorly executed in other AAC apps. And, because it should be an app that any caregiver would be comfortable downloading to their mobile phones, it would be designed for mobile phone first, rather than for tablet.

Prototype

Stakeholder feedback of my sketches led me to understand that each completed interaction in the app should never be more than three steps deep, and that repetition is key. Everyone agreed that giving users the ability to review and confirm their choices at each step could lead to the development of thought patterns in the minds of cognitively impaired individuals that might later become generalized outside of the app.

Created in Adobe Photoshop

User testing showed that subjects who previously felt disconnected from other AAC devices illustrated a willingness to engage with the prototype, and the ability to complete three-step interactions within the app.

Style Guide

In Future Sprints

• The addition of time-based data processing and machine learning, so that the app will serve up selections to choose from based on time of day, as well as the user's previous selections

• The ability for users to upload their own images and link them to customized three-step workflows

See Other Work